“Being Bipolar”: A Cautionary Tale in Bad Digital Research Ethics

Personal blogs are an act of communion, an act of humanity, the sharing of your story with another person. We each contain within us a private cosmos, and when we write ourselves, we make visible the constellations that constitute our experience and identity. However, there are many ways that these stories can lead to harm People who blog about mental illness are vulnerable to many types of harm, and unfortunately, sometimes those harms come from their “allies.”

Nowhere is this made more evident than in the article “Being Bipolar: A Qualitative Analysis of the Experience of Bipolar Disorder as Described in Internet Blogs,” published in the Journal of Mental Health Nursing in September 2017. This qualitative study—lead by renowned psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff with Anika Mandla and Jo Billings—analyzed a small sample of personal blogs written by self-identified bipolar disorder sufferers.

The authors in this study—authoritative, supposedly impartial and identity-less—undertook a thematic analysis of relevant material in personal blogs about the experience of bipolar disorder, including blogs from bipolar blogging networks, and critically examine the arguments used in support of and in opposition to mainstream conceptions based on the medical model. In reality, this research reflects a tremendously unethical, exploitative, co-option by the authors—insidiously occurring under the guise of welcoming and embracing knowledge.

Stories about mental illness belong to different domains of experience, but they have one thing in common: the people they belong to are seldom engaged with as authentic and credible thinkers, philosophers, or experts. While no means unique in its use of social media for data mining, this study functions as an up-to-date exemplar of vapid online research practices concerning marginalized groups.

Why “Being Bipolar” is Such an Unethical Study, And Why We Should Care

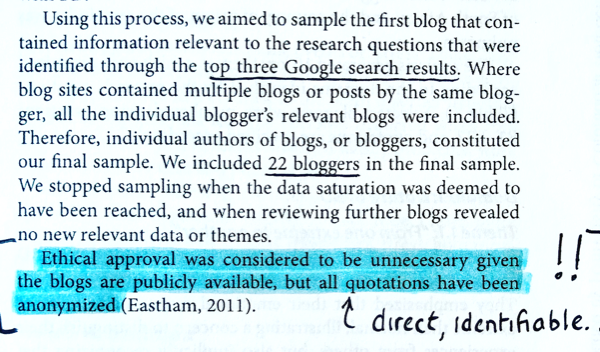

Let’s begin with the most succinct and disturbing sentence of the study which clarifies the authors’ cavalier approach to ethics:

“Ethical approval was considered to be unnecessary given the blogs are publicly available, but all quotations have been anonymized.”

As a careful reader, you might well be wondering how one can anonymize direct quotations, and the answer is: you can’t. There’s no such thing as an anonymized direct quote of an internet source. What the authors have done is merely produce an illusion of anonymity, and they’re done it poorly. The decision to pseudoanonymize subjects might be anodyne, but it also seems to indicate that the authors were not fully invested in their belief that personal blogs on mental illness are entirely of the public sphere.

There is much disagreement on whether content on publicly accessible personal blogs should be considered as freely available for any researcher to use. On the one side are those who take an almost laissez-faire view and see anything published on blogs as “fair game” for research purposes. Inherent in this view is the belief that authors have no reasonable expectations of privacy. On the other side are those understand that digital technology and culture have blurred the boundaries of privacy requiring more nuanced, fluid, and contextual conceptions.

The authors are in the first camp. They take an individualistic approach to privacy, despite the fact that, historically, socially, and politically vulnerable subjects haven’t been granted the same “right” to privacy as dominant groups—either offline or online.

They consider bloggers to be ultimate arbitrators of their fate, fully assuming all concurrent risks and potential harms that may come to them since they made the decision to post sensitive data in a publicly accessible space.

By this logic, bloggers with mental illness are not only responsible for paranoid caution and isolation from online communities, but the perpetrators (the authors) themselves bear no responsibility for predatory behavior. That kind of logic is how the criminal justice system falls apart.

“It isn’t the burglar’s responsibility for robbery if you didn’t exercise due diligence and hire a guard or invest in a security system.”

“We can’t try this murderer because you didn’t wear a bulletproof vest and helmet when you left the house this morning.”

The belief that individuals are responsible for the overcoming external harms levied against them is a theme throughout this paper.

The Worst Myth of Mental Illness

Running alongside this rejection of an ethical obligation to protect their subjects, is the authors’ sanctimonious, distorted, and offensive characterization of their blogs.

First up is the moralizing. According to the authors, a professional or self-imposed diagnosis of bipolar disorder is “real” in the biological sense but as functions morally in ways that enable “people to extrude unwanted parts of their personality into their ‘illness’.” In other words, when it’s taken up or diagnosed as a legitimate psychiatric disorder, “bipolar identity” is nothing more than a weakness of will; a crutch sufferers use to obfuscate “extreme, bizarre, usually dysfunctional and sometimes unfathomable manifestations of human agency.”

This is a bold and sanctimonious stance. The basis for a person’s character flaw? According to the authors, it can be gleaned by how bloggers attach themselves to their diagnosis.

The thing is, though, mentally ill people aren’t the ones making ourselves all about our illnesses. It’s people like the authors who choose to decontextualize and extrapolate from blogs about mental illness that make us all about our illness. In the context of this study, the experiences penned by bloggers who self-label with a “bipolar identity” are invented out of whole cloth, with no apparent connection to the circumstances of their lives—presented without race, class, gender, sexuality, or disability. The testimony of their lived experience is disembodied, decontextualized, and misrepresented by the authors with the assumption that these blogs reflect a consistent singular identity within and across bloggers.

Scientific Merit

Obtaining quality data and analyzing it properly is an essential component of ethically defensible research. Unfortunately, the authors seem to have gotten short with the truth and have interpreted bloggers’ words in value-laden and irresponsible ways.

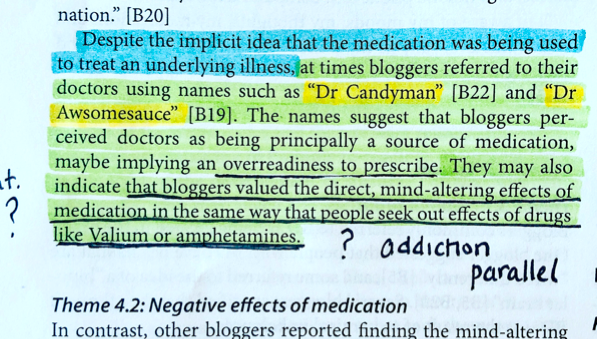

Consider the following interpretation, extracted from the paper:

“Despite the implicit idea that the medication was being used to treat an underlying illness, at times bloggers referred to their doctors using names such as “Dr Candyman” [B22] and “Dr Awesomesauce” [B19]. The names suggest that bloggers perceived doctors as being principally a source of medication, implying an overreadiness to prescribe. They may also indicate that bloggers valued the direct, mind-altering effects of medication in the same way that people seek out effects of drugs like Valium or amphetamines.”

Oceans of contempt and nonsense, all wrapped up in three sentences. I’ve read the blogs from which these quotes are taken and they do not “suggest” or “indicate” any of this.

The word “awesomesauce” (extremely good; excellent) was officially added to the Oxford English Dictionary in three years ago. Before that it held the same meaning as lighthearted slang. In the original entry, Dr. Awesomesauce exists in relation to Dr. Goodenough, and the author is hyperaware and concerned with being overmedicated. Of note, is the reference to an internalized stigma due to feeling like a “personal failure” for needing an antipsychotic.

While Dr. Candyman may seem like less of a stretch for describing an over-prescribing physician, the context of the entry is important. Here, the blogger is writing about two providers: psychiatrist (Dr. Candyman) and psychotherapist. More importantly, Dr. Candyman is described as providing helpful advice in finding a therapist. There is not a single mention of medication. The reasonable conclusion is this is lighthearted, sarcastic nickname for a medical doctor.

Let’s be absolutely clear about what’s happening here: the authors’ presented two bloggers’ nicknames for their psychiatrists and drew a straight line to a celebration of medication. This magnificently premature and misleading. They then make an interesting parallel to addiction and end with the conclusion that these bloggers may be opportunistic junkies.

The message is clear: these bloggers are manipulating a diagnostic identity in order to get drugs (which by their accounts made them feel terrible). We can take this even further to suggests that people with bipolar disorder disobey an authority and a legal system already in place to obtain “mind-altering” drugs that they don’t really need. The implicit assumption is that these bloggers might be criminals—in a judicial system already betrays people it purports to protect against racist, ableist, and classist favoring.

I am frustrated at the authors’ insouciance. Their cherry-picking for punctiform one-liners and contrived examples. These matter-of-fact assertions of less-than-obvious generalizations absent any elaboration are patterned in strange and increasingly troubling ways culminating into such a cataclysmically myopic paper. This is shameful. These quotations are embodied and situated in deeply authentic narratives that belie any of the authors’ defamatory and unprofessional interpretations/conclusions.

If you attribute an individuals’ character to her mental illness, you’re placing the responsibility for its existence squarely on her. It isn’t an oppressed person’s duty to survive and shoulder responsibility for mental illness. That idea itself is violent. However, the authors take their gaslighting much further by enacting violent and disciplinary reactions to their subjects.

Fake News

Donald Trump’s deployment of “fake news”—an abusive static logic that combines habitual lying, invalidation of trauma, a refusal to be held accountable for his statements, and skepticism of the media—presents a clear example of gaslighting in action. But Trump’s use of false rhetoric has been well-covered. More subtle yet nevertheless insidious is the gaslighting performed by the Moncrieff and colleagues, and those who defend their claims. The authors, for the most part, have been widely-revered by cis white middle-class Eurocentric circles, treated as renowned scholars, radical advocates, or personal heroes than the embodiment of harm.

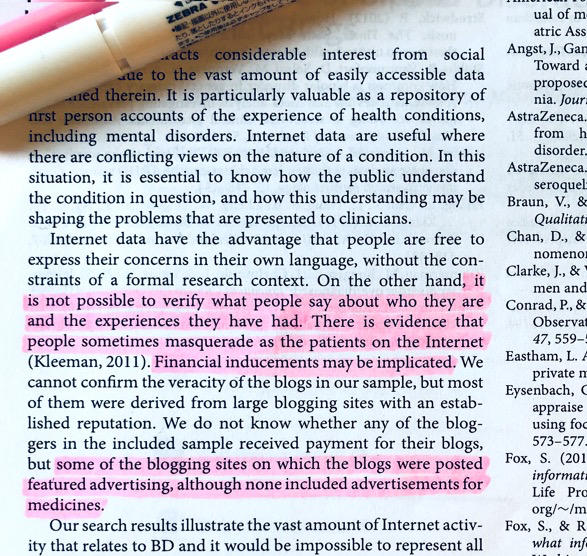

The authors’ conviction that bipolar disorder is not only over-described and over-prescribed, but also not a “real” bodily illness at all, is a belief that brings them into direct opposition with the experiences of their subjects. Nowhere is this more apparent than the authors’ skepticism and credulity about the motivations of those who write about their experiences with mental illness (and blogging) is described in the following excerpt (emphasis mine):

“Internet data have the advantage that people are free to express their concerns in their own language, without the constraints of a formal research context. On the other hand, it is not possible to verify what people say about who they are and the experiences they have had. There is evidence that people sometimes masquerade as the patients on Internet(Kleeman, 2011). Financial inducements may be implicated. We cannot confirm the veracity of the blogs in our sample, but most of them were derived from large blogging sites with an established reputation. We do not know whether any of the bloggers in the included sample received payment for their blogs, but some of the blogging sites on which the blogs were posted featured advertising, although none included advertisements for medicines.”

To sum up: they illustrate how well they listen to their subjects: the authors first suggest they aren’t even real people, then suggest they are acting deceptively by faking their distress for attention or personal gain (supported with a citation for an article on Munchausen syndrome, itself a psychiatric diagnosis for people who “play sick” for sympathy or attention). All the while, they cite the motive for profit as if to imply that writing deeply personal illness narratives on bipolar disorder blogging networks is a lucrative venture.

If the authors are studying the representation of “bipolar identity” on blogs written by self-described sufferers, then how are concerns on “fake distress” and “malingering patients” even relevant? For instance, even if a person is choosing a fictitious identity or creating a fictitious literary narrative, the desire is real and culturally significant. The authors seem to state this themselves in the next paragraph where they justify the importance of their research, as depicted below (emphasis mine):

“[S]ince the included blogs were easily accessed, whether or not they were genuine or representative, their content is important because it is likely to exert a disproportionate influence over public views.”

It’s one of many interesting contradictions and rhetorical moves in this study. These aren’t mistakes. This is deliberate and formulaic; they are following an unoriginal pattern of omission in order to misrepresent. Bourgeois academics like Moncrieff are deliberately vague, elaborating as little as possible and often time not at all. The contradictions are tactical and instrumental ways to direct a particular narrative. On the one hand, we’re meant to blame the bloggers for being manipulative and to sympathize with the authors (the obvious subtext). But the ending context about mental health stigma and discrimination was somehow not connected to the story at all?

The takeaway from this is for “normal” people to be skeptical of people with bipolar disorder for their “mental illness deception,” especially within a binarized and medicalized space, not a nuanced and balanced piece of straightforward reporting about blogs and identity. This is gross. This is harmful and amoral research that also lacks any validity or utility since the data analysis is inflected with the authors value-system.

Everything about this study is condescending and invalidating. The intellectual and practical dangers in this bootstrap rhetoric and moral model approach to mental illness reflects the same problematic logic of the medical model. They both employ the same oppressive logics to pathologize suffering and locate deviancy within an individual. Both perceive suffering and distress as “all in one’s head.” Both are harsh on the individual and soft on the social. This can be most clearly seen in the way the authors’ question the legitimacy of bloggers suffering: a move that only makes sense when you evacuate the politics of now from culpability and place the onus of well-being squarely on the individual.

What a lot of victim blaming and shaming people don’t understand is how mentally exhausting it is to never stop blaming yourself for your victimization. They don’t understand how terrifying it is to enter a space and be hyper-vigilant because you are solely responsible for the harm that befalls you. The internalized shame, guilt, and external shame that comes with consuming psychiatric medication is not unfamiliar to anyone with mental illness, including the bloggers under study.

At the risk of making this too much about me, I need to make my beliefs and reasons clear, such as they are (and were):

- I suffer from schizophrenia, or, as the authors of this study put it, “no I don’t.”

- I don’t like being spoken for.

- Whenever I hear the “mental illness is a myth” song, my ears shut down. I do not agree with the reasoning or the world view it produces.

- I do not believe that mental illness is a character flaw or a moral thermometer (but being sanctimonious and condescending toward people with mental illness/accusing them of faking for attention certainly is).

I know from experience that when I stop taking my medication I cannot function: I cannot move and no amount of validation, hugs, therapy, yoga, or aromatherapy can change that. That’s just me. I do not take my medication to get high; I just want to not kill myself. Like many people, I hate being on them. Relying on potent, mind-altering substances to function produces no small amount of shame, not to mention existential anxiety. I’ve tried to go off them many times in the hopes that the “real me” will finally be able to stand on her own. Each time, I run into the heartbreaking reality that my unaltered self is too painful to bear. This is not theoretical. I know this subject.

That said, this need to be said too: I’ve become perceptive to academics who appear to be doing the right thing while leveraging trauma for gain. Again, this is gross. And inexcusable.

Reimagining Ethical Research Online

There’s an urgent need to recognize the ways that we as researchers of vulnerable and stigmatized subjects reproduce and escalate harm and capitalize on (rather than care for) sensitive and identifiable data. This requires reflexivity at every step.

Water (and cats) flow into the shape of their container. And the internet has vastly changed the shape of the container. Our lives are contoured to the unique contexts into which we are born and reside which themselves shape our actions, emotions, and mindsets. Personal blogs and social media change the way we build relationships, share information, and make everyday decisions, including decisions about health and wellbeing.

It seems that many researchers want to find the “right way” to conduct research, by which they mean they want to check a bunch of boxes that will reassure them that it’s allowed and passable, without considering the possibility that maybe they just don’t do the research. There is a kind of colonial/white supremacist (and I think deeply patriarchal) stance which presumes that everyone ought to be able to study everything and I just think that all arguments that proceed from that premise are deeply flawed.

We need to understand that not every blog post or tweet is “for” us just because we can access it. We aren’t always the audience and therefore don’t always deserve extended explanations or history/context we’ve missed. When the content is of a sensitive or risky nature or involves marginalized identities, we need to consider whether we have a right to research at all.

Careful and respectful research can be done in ways that produce valuable knowledge, but they must foremost be motivated by an ethical commitment to participants and the desire to respect their knowledge and experiences. De-anonymization, the phenomenon of doxxing, harassment, and stalking are all live and urgent concerns on social media. It’s upsetting that our society and culture contains a seemingly endless supply of ways to make marginalized people feel unsafe and unwelcome. On the flipside, online spaces are emancipatory too. But it must be understood that public information exists in the context of power and consent, and we must construct our ethics in that context. The impulse, when an encounter between a human and theory goes badly, is to extract a lesson, but what moral can you draw from an encounter like this? That will be explored in Part 2.