I recently published “Are You Really Trans?”: The Problems with Trans Brain Science on the International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics (IJFAB) blog.

I recently wrote about “Why Trans Exclusionary Feminism is Bad for Everyone” on the International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics (IJFAB) blog.

In which I comment on feminist bioethics, relational autonomy, medical undiagnosed symptoms, and diagnostic uncertainty in The American Journal of Bioethics.

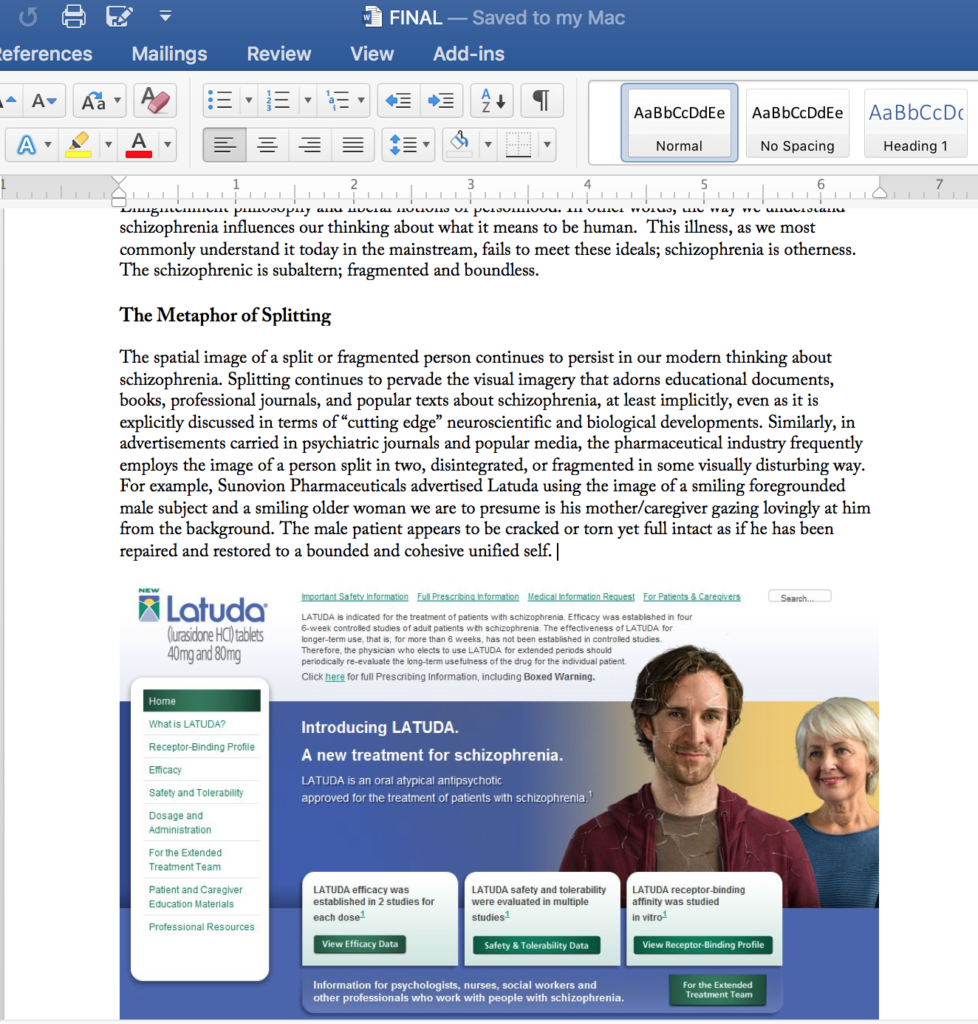

The Metaphor of Splitting

It’s everywhere.

As I glance down the barrel of academic deadline, I am trying to go somewhere with the splitting metaphor in schizophrenia as it relates to narratives of modern scientific objectivity, unity, progress, and purity. It’s very much a mess but one thing I’ve found is that this metaphor, for as much as it’s been dismissed in psychiatry and psychology circles, still has incredible currency in both professional literature and popular culture. It’s literally everywhere. On the covers of books, Schizophrenia Bulletin, professional and popular journals, mainstream news media, pharma ads, etc. It’s… interesting.

Barriers and Belonging

A much needed narrative anthology representative of a vast array of embodied disability experiences.

Jarman, Michelle, Monaghan, Leila, and Alison Quaggin Harkin (Editors). Barriers and Belonging: Personal Narratives of Disability. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2017.

My review of this book is on Metapsychology Online Reviews.

The Minority Body

Philosopher Elizabeth Barnes proposes a value-neutral model of disability

Barnes, Elizabeth. The Minority Body: A Theory of Disability. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

“It’s easy to confuse the view from normal with the view from nowhere. And then it’s uniquely the minority voices which we single out as biased or lacking objectivity” (p. ix).

Philosopher Elizabeth Barnes begins her book with a personal and perhaps, defiant acknowledgement: “This book is personal…I’m disabled, and this book is about disability. Of course it’s personal” (p. ix). However, it can also be claimed that philosophy of disability is personal for everyone because non-disabled people are just as emotionally invested in being non-disabled. Thus, the view from normal is never the view from nowhere.

In The Minority Body, Barnes’s central question concerns the connection between disability (physical, she does not talk about intellectual or psychiatric disability) and well-being. As an analytic philosopher, Barnes describes frustration at the explicitly normative and negative prevailing characterization of disability within her discipline. The characterization of disability in both academic philosophy and contemporary society views disability in terms of loss, tragedy, and misfortune. In response, Barnes develops an alternative understanding of disability to compete with the prevailing disability as always sub-optimal ideology. Her model is based on understanding disability as a social identity that exists as a state of difference, not defect. She describes the experience of being disabled as having a minority body: a body that is different but not intrinsically worse in any way.

In Chapter One: “Constructing Disability,” Barnes begins with conceptual questions about what disability is and seeks to develop a unifying account of disability that meets the following criteria: (i) it delivers correct verdicts for paradigm cases, (ii) it doesn’t prejudice normative issues, (iii) it’s unifying and explanatory, and Iiv) it’s not circular (pp. 10-13). She chooses to exclusively focus on physical disability and offers no promises that her model will be applicable to cases of psychiatric disability or cognitive disability. She surveys (and rejects) biological, naturalistic accounts of disability that attempt to locate disability as an inherent feature of individual bodies, dismissing the idea that disabilities are natural kinds (p. 23). She next looks to models of disability based on social constructionism and outright dismisses a purely social model of disability as being overly disembodied as well as maintaining an unclear distinction/difference between impairment and disability. She maintains that social constructionist accounts of disability have “gone too far” in removing the body entirely from accounts of disability. According to Barnes, it is entirely permissible to assert something is socially constructed and objectively real. In other words, social construction and the objective features that are emblematic of what disabled bodies are like are not mutually exclusive. As a result, she offers a “moderate social constructionism” model of disability “that says that disability is socially constructed, but which places greater importance on objective features of bodies (rather than how bodies are perceived or treated)” (p. 38). She writes, “Being disabled is not merely a matter of what your body is like, but we can still allow that it is partly a matter of what your body is like” (p. 37). In this model, disability is a property of bodies, but it’s a socially constructed property of bodies. She argues that this moderate social constructionist view can make sense of both the objective realities of disabled bodies and how those bodies are viewed socially. Lastly, she argues that an account of disability must be informed by the disability rights movement, who she argues didn’t just influence the category of disability, but created it. According to Barnes, disability activists are best positioned to determine what bodies should be considered disabled due to their unique first-hand knowledge of the experience of disability. As a result, she advances a moderate social constructionist account of disability that arises from and is mediated by social solidarity. Her contention is that what disability is are those things that the disability rights movement is promoting justice for (p. 43). On this account, disability is a “rule-based solidarity among people with certain kinds of bodies” (p. 46).

In Chapter Two: “Bad-Difference and Mere-Difference” and Chapter Three: “The Value-Neutral Model,” Barnes further refines her characterization of disability in contrast to the contention that disability is something that by itself intrinsically makes a person worse off. She distinguishes between bad-difference and mere-difference views of disability and argues that many non-disabled people, including many philosophers, take some version of the bad-difference view as just common sense. Bad-difference views of disability claim that, even in a society free from ableism, there will still be “a negative connection between disability and well-being” (p. 71). Barnes points to the vast amount of evidence suggesting that non-disabled people tend to assume incorrectly how disability affects the perceived well-being of disabled individuals, arguing that non-disabled people tend “to systematically overstate the bad effects of disability on perceived well-being and happiness” (p. 71). She makes the claim that rather than bad-difference, disability is an example of “mere difference,” not intrinsically negative or positive with respect to well-being. Disability is something that absolutely that makes you different in the way that gender identity, sexual orientation, and race make you different, but it is not disadvantage and “there’s no essential link between disability, disadvantage, or stigma” (p. 51). Barnes argues for a value-neutral version of the mere difference view of disability premised on the idea that disability by itself does not have any intrinsic connection to well-being. She argues that this value-neutral model provides a more nuanced view of disability that’s missing in other theories. Ultimately, what makes disability a net positive or net negative in particular cases is determined not by the mere presence of disability, but by how disability combines with other intrinsic and extrinsic circumstances of a person’s life. Critically, the mere-difference view allows for disability to adversely affect a local person’s well-being, but not a person’s overall quality of life. Barnes distinguishes between local bads and global bads to make this point:

some things are bad [or good] for you on the whole or all things considered. Other things are bad [or good] for you with respect to certain aspects of your life or with respect to certain times (p. 80).

She argues that most of the bad things disabilities people associate with their disabilities constitute local bads and do not affect the overall value of a person’s life (i.e., they are not globally bad). She believes that philosophers (and many others) have a tendency to collapse local into global bads which leads to their contention that disability is “bad simpliciter” (p. 84). Instead, she argues that:

Disability is a neutral simpliciter. It can sometimes be bad for you—depending on what (intrinsic or extrinsic) factors it is combined with. But it can also, in different combinations, be good for you. And all of that is compatible with disability sometimes—perhaps always—being locally bad for you (that is, bad for you with respect to particular things or particular times) (p. 88).

It’s important to recognize that this view of disability is consistent with disability being a harm in a restricted sense (with respect to some time and some feature) and with disability on the whole being bad for some people, depending on what it’s combined with. It is also consistent with disability being something that makes some people’s lives go better.

In Chapter Four: “Taking Their Word For It,” Barnes bolsters her value-neutral model disability with the first-person testimony of disabled individuals. The testimony she presents from disabled activists clearly demonstrates their experience of well-being to be on par with that of non-disabled individuals. According to the testimony of a number of disability activists, disability is not a private tragedy, but a “complex, multifaceted experience” that can be valuable and associated with a positive experience of well-being. Nevertheless, it remains a dominant belief among philosophers and mainstream bioethicists that disabled people have a much lower level of well-being than non-disabled people and even when confronted with evidence to the contrary, they do not change their views, but instead write them off as unreliable or uninformed. The dismissals of these first-person experiences are an example of “testimonial injustice” following philosopher Miranda Fricker (p. 120). Testimonial injustice occurs when “a speaker is not believed or given due credence (where others would be) specifically because they are a member of a group that is the subject of stigma” (p. 135). In doing so, a person engages in “identity prejudice” in that they judge someone to be the kind of person who is unreliable.

Barnes argues that the testimony of disabled individuals is often dismissed with appeals to adaptive preference. According to the model popularized by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, preferences are adaptive when they are formed toward something sub-optimal as a result of a constraint on options. Barnes writes: “We are saying, in effect, that the non-disabled—the majority—are in a better position than the disabled—the minority—to evaluate disabled people’s well-being” (p. 133). This is a serious claim and one with an “unhappy history” (p. 133). The problem with the adaptive preference model is that it allows us to discount some testimony as irrational or misleading and can quickly become a tool to maintain the status quo.

In Chapter Five: “Causing Disability,” Barnes addresses causation-based objections that typically arise from a neutral or positive valuing of disability. Philosopher critics have objected that a mere-difference view of disability licenses the permissibility of causing disability and the impermissibility of removing disability. Barnes argues that this philosophical claim that disability is bad-difference rests on intuition and is highly suspect especially “when it contravenes the testimony of many members of that disadvantaged group” (p. 72). This brings up important points regarding so-called “common sense” intuitions about disability advanced by non-disabled “experts.” Barnes argues that contrary to “common sense” views of disability, it is actually very difficult to put flesh on the bones of the argument that disability makes a person worse off. It is much less obvious to make the claim that disability is still tightly correlated with negative experience even in the absence of ableism.

Finally, Chapter Six: “Disability Pride,” Barnes argues for the importance of disability pride movements. The disability rights movement is a civil rights movement on par with gay rights, women’s rights, and racial liberation movements. She articulates the disability pride as “the politically motivated celebration of difference” (p. 181). In an ableist society that endorses negative stereotypes and stigma about disability, it can become easy to feel as though disability is a private tragedy. She argues that disability pride makes emotional room to celebrate disability as a contributing factor to human flourishing, but that these movements are also epistemic: “ pride movements also affect what we can know” (p. 183).

Barnes introduces Fricker’s concept of hermeneutical injustice. Barnes summarizes the idea:

In cases of hermeneutical injustice, we harm people by obscuring aspects of their own experience. Our dominant schemas—our assumptions, what we take as common ground—about a particular group can make it difficult for members of that group to understand or articulate their own experiences qua members of that group (p. 169).

Hermeneutical injustice describes the phenomenon where an individual finds it hard to know or articulate things about themselves and their own social experience due to prejudices and stereotypes about the kind of person that they are. Disabled people experience hermeneutical injustice, insofar as they are forced to try and understand and articulate their experiences using the dominant conceptual tools which are often disability-negative. In other words, this injustice occurred in the context where disability was conceptualized and understood not by the lived experiences of disabled individuals but a privileged hegemonic understanding of what disability is. This understanding by a non-disabled, majority group then influences dominant norms and schemas about disability which make it difficult for disabled people to understand and articulate their own experiences.

Thoughts

- I’m inspired by Barnes expressing her infuriation with academic philosophy and it’s understanding of disability.

- All of the testimony Barnes presents to bolster her argument comes from disability activists and not the general disabled population. All of these activists claim value in their disability. Yet Barnes also clarifies at many points in the book that there are many disabled people who do not describe their disability as a positive experience and would prefer not to be disabled. It seems like like a strange flaw then that she would prefer to ignore these testimonies or those from the general disabled public. It makes me wonder whose testimony counts?

- The majority of her examples seem to showcase disability through paradigms such as blindness, deafness, and mobility impairments. I am curious about how testimony might change for someone with chronic fatigue syndrome or a painful physical condition.

- Barnes contrasts disability with cancer, claiming that there is no value in having cancer whereas there is for some disabled people who find value in their disability. So, disabilities are not cancer. But is this right? Might someone not find value in their cancer in the way they do with disabilities? Or what about people with Munchausen syndrome?

- Many disability scholars make it a point to note that the majority of individuals will experience disability at some point in their lives. This seems to make it distinct from other minority identities like being gay or being a woman.

- Barnes says that first person testimony doesn’t have to be upheld as sacrosanct, but in my personal experience “compromising” normally means silencing the already oppressed parts of myself. When you are up against an oppressor who willfully wants to deny your humanity, the moment you begin to accept compromise, you are most vulnerable to epistemic violence.

- Despite Barnes’ explicit acknowledgement of her wish to focus exclusively on physical disability, I wonder if this choice reinforces a hierarchy or ideology within the disability community.

Beyond Schizophrenia

An interesting and important book on political economy and serious mental illness.

Baldwin, Marjorie L. Beyond Schizophrenia: Living and Working with a Serious Mental Illness. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

My write-up on Metapsychology Online Reviews, along with a few of my cringey typos.

The Case for Conserving Disability

Notes on Rosemarie Garland-Thomson’s fantastic article.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. “The Case for Conserving Disability.” Bioethical Inquiry 9, no. 3 (2012): 339-355.

The historical and ideological trope (described by David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder) that disability disqualifies people from participation in society is a commonly held view of disability in our society. According to disability studies scholar and bioethicist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, this understanding of disability is rooted in eugenic logic, which “tells us that our world would be a better place without disability” and promotes efforts for its elimination (pp. 340-341). In this article, Garland-Thomson explores “the bioethical question of why we might want to conserve rather than eliminate disability from the human condition” (p. 341). She argues that rather than repeat claims that conceptualize disability as disqualification, where it is only associated with “pain, disease, suffering, functional limitation, abnormality, dependence, social stigma, and economic disadvantage,” disability should be reconsidered in terms of the benefit it bestows on society and therefore should be conserved: preserved intact, kept alive, and encouraged to flourish. She employs the language of environmental conservation intentionally to suggest that rather than being a restrictive liability, disability is a generative and beneficial resource that brings diversity to the human experience. Considering “the cultural and material contribution disability offers the world,” Garland-Thomson calls on disability to be celebrated and valued as a good in itself rather than just protected for its presumed fragility and vulnerability (p. 341). Employing counter-eugenic logic, she argues that disability provides humankind with invaluable resources in three interrelated areas: narrative, epistemology, and ethics.

What is Disability?

It’s first important to understand how Garland-Thomson goes about defining disability. She provides both a political and cultural definition of the term. For a political definition, she turns to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 and the United Nations Convention of Rights of People with Disabilities of 2009 to highlight how each is dependent on a medical model of disability. For her preferred cultural definition of disability, she draws on phenomenology and constructivist understandings of disability in terms of “identity, materiality, and being” (p. 342) and argues that “what we think of as disability begins in bodily variation and the inherent dynamism of the flesh” (p. 342). In other words, disability can be understood in how the body is continuously transformed in its interactions with the environment over time. Because “we are fragile, limited, and pliable in the face of life itself,” Garland-Thomson argues that we “evolve into disability.” As a result, “disability is perhaps the essential characteristic of being human” (p. 342).

Disability as a Resource

People with disabilities enrich the world, not necessarily or only through economic contributions, but simply through their presence. This is what she calls her “because-of-rather-than-in-spite-of counter-eugenic position” (p. 343). Garland-Thomson argues that “as both a generative concept and a fundamental human experience,” disability has the potential to make meaning through three interrelated ways: life narratives, knowledge production, and ethical insight.

Disability as a Narrative Resource

Disability can help convey human stories. In discussing disability as a narrative resource, Garland-Thomson refers to Leslie Fiedler’s 1978 book, Freaks: Myths and Images of the Secret Self, and Arthur W. Frank’s 1995 book, The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness and Ethics. She argues that disability narratives contribute to “the cultural work of teaching the nondisabled to be more human” (p. 344). Fielder seeks to preserve “extravagant disability in the world” through disability-as-freakdom that raises consciousness in the nondisabled that enables them to become more human through self-awareness. “For Fielder,” she writes, “people with extravagantly manifest disabilities should inhabit the world to provide theatrical, edifying encounters between ordinary folk dulled by the ordinary, needing an abrupt consciousness-raising exercise to be awakened to their own internal monster” (p. 344). For Frank, disability is a narrative resource in the form of self-story. Frank sees disability as a resource for disabled people and asserts that first-person narrative has a restorative power because it enriches self-understanding and identity formation for people who have been thrust into a sick role. “Crucial to both Fiedler’s and Frank’s accounts of disability as a narrative resource,” she argues, is the idea of “suffering as ennobling” (p. 345).

Disability as Epistemic Resource

Because of being disabled, not in spite of it, the disabled have unique experiences in this world compared to the nondisabled population, and therefore the disability and the experience of being disabled are a resource for novel insights and knowledge that only be gained because of the disability. Garland-Thomson references the 2008 book, Disability Bioethics: Moral Bodies, Moral Difference by Jackie Leach Scully to describe the ways that disabled bodies create “ways of knowing shaped by embodiment that are distinctive from the ways of knowing that a nondisabled body develops as it interacts with a world built to accommodate it” (p. 346). Garland-Thomson provides the example of deaf-blind activist and writer, Helen Keller, who generated “alternative or minority ways of knowing” (p. 346) when her other senses were heightened. The result was a novel way of experiencing the world not available to the nondisabled.

Disability as Ethical Resource

In her discussion of disability as an ethical resource, Garland-Thomson refers to Michael J. Sandel’s 2007 book, The Case Against Perfection: Ethics in the Age of Genetic Engineering. Sandel describes disabilities, particularly children born with disabilities, as unique ethical opportunities that allow us to “appreciate children as gifts” and to accept them “as they come” without controlling intervention or desire to interfere in some way with their inherent humanness (p. 347). Sandel vies the modern impulse to control or restrict as reflecting our hubris and narcissism and believes the cultural work of disability is to defeat this self-aggrandizement and getting back to “an appreciation of the gifted character” of humans as they exist. His rationale for conserving disability is similar to Fiedler’s in suggesting that the disabled can help make the nondisabled into better people by teaching them about what it means to be human.

Counter-Eugenic Logic and the Problem of Suffering

It is well-established that nondisabled people have a much harsher view of what suffering entails for those with disabilities than the people who actually live with disability. The prevention of suffering is one of the most popular eugenic arguments for eliminating disability (and disabled people), but concepts of who actually suffers and how much are widely misunderstood by nondisabled individuals. Many other groups including bioethicists, supporters of physician-assisted suicide, and the reproductive rights movement have used this logic of preventing suffering for making their case in eliminating disability. Often times, empathy underscores these concerns, but the problem with empathy is that it “depends upon the experiences and imagination of the empathizer in regarding another person, prejudices, limited understandings, and narrow expectations can lead one person to project oversimplified or inaccurate assessments of life quality or suffering onto another person” (p. 350). At the extreme, this can lead to “mercy killings,” and it often results in an underestimation about the quality of life of those with disabilities. Through the heartbreaking story of Emily Rupp’s experience of parenting a child with Tay-Sachs disease, Garland-Thomson demonstrates how “suffering expands our imagination about what we can endure” (p. 350). Another benefit of disability that Garland-Thomson gains from Rupp’s experience is that disability has the power to compel us to forget about the future and live in the present tense. Disability therefore flies in the face of modernity, which relies on “a temporal aspiration” (p. 352) due to its unpredictable and uncontrollable nature. Disability then, according to Garland-Thomson, is “a conceptual category that represents something going beyond actual people with disabilities” (p. 352). According to Garland-Thomson, “disability and illness frustrate modernity’s investment in controlling the future” (p. 352).

My Concerns/Questions

What about disabled people who are unwilling to endure the downsides of disability that a movement towards conservation would bring?

In The Wounded Storyteller, Arthur Frank writes about illness self-narratives and not disability specifically. He also describes self-narrative as a way of gaining control over contingency and talks a lot of about crossing a divide between sickness and health and of remission society where “the foreground and background of sickness and health constantly shade into each other.”[ref]Frank, Arthur W. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness and Ethics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013: 9.[/ref] Are there any complications here with regards to Garland-Thomson’s use of Frank as an example?

Invisible Disabilities

N. Ann Davis presents a philosophical and sociological exploration of the concept of disability.

Davis, N. Ann. “Invisible Disability.” Ethics 116, no. 1 (2005): 153-213.

In this article, philosopher N. Ann Davis critically reflects on how difficulties faced by people with invisible disabilities can provide us with a better understanding and appreciation for how normative and deeply flawed our prevailing understandings of disability are.

Human Paradigms and Prevailing Ideologies

Paradigms are associated with particular assumptions about the world. Davis explains that fundamental beliefs about what human beings are and what they should be are expressively embodied in a society’s “human paradigm.” Our society’s human paradigm assigns primacy to meeting able-bodied standards. This paradigm treats being able-bodied as both normal and normative. The flip side of this is that, absent a clear marker of disability, the assumption is made that disabled individuals occupy an “unnatural” or “abnormal” state of human existence. Our human paradigm shapes all aspects of life from directing our personal choices to shaping our institutions and policies. It also gives substance to our understanding of “fulcral concepts like wellness and illness, health and disease, and ability and disability” (p. 157). The presumption that there are deep and obvious differences between being “normal” and being disabled is taken as self-evident and factual. But facts do not speak for themselves . One might consider whether a body without a single impairment exists? Defining disability in terms of ability and disability encourages the exaggeration of difference by nature of their binary opposition. This “commonsense” relationship has been accorded importance by a particular society that has embedded the value into its institutions, policies, and social discourse.

Like other forms of prejudice, ableism rests on a number of largely unchallenged assumptions that inform understandings of disability:

The first is that it is normal for humans to be able-bodied. The second is that a person’s disability is a consequence of (or results from) his or her not being able-bodied. The third is that it is principally their abnormality (or their not being able-bodied) that explains why those who are disabled suffer disadvantage in society: both the suffering and the disadvantage of those who are disabled are natural in the sense that they are consequences of the fact that their bodies are defective in certain respects (p. 164).

The result is a “deficient and defective” (p. 213) understanding of disability and of disabled individuals in terms of purely physical or “objective” standards that sees disadvantage as a natural consequence of the fact that they are disabled (p. 157). Widespread subscription to an ableist ideology that claims disadvantage is due to abnormality inherent in disabled individuals rather than a society’s policies and practices has resulted in a minority status being accorded to disability. Those who are believed to be in a minority are more likely to be disadvantaged in some way and this disadvantage is thought to stem directly from their inherent deviance rather than the social practices that exclude them. The exaggeration of difference between the polarizing concepts of ability and disability and normality and abnormality makes disability seem exceptional and unusual. According to Davis, such a view might explain why there has been a reluctance to endorse policies of accommodation that would make life easier and better for people with disabilities (and those who interact with them): “if they take abnormality to imply rarity, then the resistance to providing more robust accommodation of people with disabilities might stem from the belief that it is only a small portion of people who would be benefited by our so doing or that it is somehow unfair to expect ‘us’ to make sacrifices to benefit ‘them’” (pp. 176-177).

Defensive Strategies

When something is terrifying enough, people seek to protect themselves by putting distance between themselves and the terrifying thing. Davis argues that the push for clear demarcation between people with visible markers (disabled) and people without visible markers (assumed nondisabled) is a defensive strategy employed by our natural tendency to deny human mortality and frailty. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum states, “Human beings are born into a world that they have not made and do not control.” [ref]Nussbaum, Martha C. Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 177. [/ref] While certain identity characteristics, like racial, ethnic, and gender categories, are considered fixed and unchanging, disability is an identity category any person can enter at any time. The longer we live, the greater are the odds that we will live some portion of our lives as disabled. Those who meet able-bodied standards now cannot expect to maintain them indefinitely. To recognize our own vulnerability and frailty involves acknowledging “that even the best-ordered, most well thought-out, and deeply considered life plans can be derailed by things that lie outside of our control, and the acknowledgment that our lives may not be seen as good by other people even when we succeed in living lives that are good by our own lights” (p. 193). According to Nussbaum, able-bodied individuals “know that their bodies are frail and vulnerable, but when they can stigmatize the physically disabled, they feel a lot better about their own human weakness.” [ref]Ibid., 219. [/ref] The defensive strategies employed by those of us who possess a socially favorable status function to create disability and further marginalize disabled individuals.

Invisible Disabilities

Davis contests the presupposition that life is easier for people with invisible disabilities by arguing the primacy of visibility has become equated with veracity of disability. “When individuals are not ‘seen’ as disabled,” Davis argues, “it can be more difficult for them to secure the assistance or accommodation they need to function effectively” (p. 154). When disabilities become less obvious, however, people receive them with increasingly skeptical stance. The skepticism that confronts a person with an invisible disability is deep and multidimensional. The specter of lack of motivation or will to change often come into play in cases where “evidence” of a person’s disability lacks an identifiable physical cause and is based exclusively on subjective reports. Davis refers to “the myth of the world-transcendent will” to describe the oft-expressed view that perceived incapacities for some individuals stem not from a true disability but from an inability to “galvanize the will” overcome their situation (p. 186). As a result, people with invisible disabilities are often subjected to a very specific ableist attitude that casts doubt upon the severity of their condition or its existence altogether. Individuals with invisible disabilities are often forced to “prove” to hostile strangers they are really disabled and not merely seeking undeserved advantages:

“They thus face a double bind: either they forgo the assistance or accommodation they need—and thus suffer the consequences of attempting to do things they may not be able to do safely by themselves—or they endure the discomfort of subjecting themselves to strangers’ interrogations. For those who are disabled, not receiving needed assistance is not merely disappointing or frustrating: it may be an insuperable obstacle or a risk to health or life” (pp. 154-155).

Having to repeatedly disclose one’s disability in an effort to get recognition and accommodation can be, as Davis writes, “an awkward and thoroughly unpleasant undertaking” (p. 205). Davis argues that “people whose disabilities are invisible are regularly put in the position of having to challenge the adequacy of our society’s human paradigm head on, and of having to confront the wall of denial that surrounds and upholds our subscription to this paradigm” (p. 205). When individuals appear to meet able-bodied standards, they are presumed to be “normal” (e.g., nondisabled). Because people with invisible disabilities can often “pass” as able-bodied, their claims to disability are often called into question and sometimes deemed unnecessary. This contributes to this group’s further exclusion and invisibility from the public sphere. The hegemony of ability and the idea of physical perfection versus defect has resulted in, to cite Nussbaum again, “the creation of two worlds: the public world of the ordinary citizen and the hidden world of people with disabilities, who are implicitly held to have no right to inhabit the public world.” [ref]Ibid., 308. [/ref]

A Posturing of Denial

Why do we continue to embrace views of disability that are based on generally unexamined and uncritical assumptions and are so clearly inhumane and morally indefensible?

Davis argues that the reason behind many prevailing views of disability and attitudes toward disabled individuals is society’s encouragement and adoption of “a deforming posture of denial” (pp. 188-189). According to Davis, when able-bodied people deny their own vulnerability and frailty, they experience a diminished humanity for people with disabilities and are less likely to want to engage with them. The result, according to Davis, is a personal and moral impoverishment:

“In continuing to advocate—or even tolerate—our society’s subscription to a human paradigm that marginalizes disabled persons, and a dominant ideology that pathologizes them, we not only harm those whom we now marginalize but also do something that threatens to make our own lives go less well by our own lights. If our society continues to marginalize and devalue those who are disabled, then it is likely that most of us will face marginalization” (p. 191).

Embracing and giving weight to the lived experience of people with disability in ways that encourages their active participation in the public realm is one small move in the right direction. In making the social realm more accessible to disabled individuals, we conceptualize disability as a benefit rather than a defect in “the richness and diversity of the human good, the multiplicity of the ways in which it can be attained, and the unduly restrictive consequences of our previous modus vivendi” (p. 201).

But an awareness is only half the battle:

“However, even if we concede that those who live in our society now nominally recognize that it is indefensible to turn away from people with disabilities, ignore them, or treat them in ways that are blatantly discriminatory, it can be argued that the defensiveness and denial implicit in our continued commitment to a human paradigm that accords so much importance to meeting able-bodied standards help to perpetuate a deeper, more insidious, and more damaging denial of the humanity of disabled persons. As a society, we have failed to recognize that the very patterns of contemporary American life and the institutions that sustain it often discount or exclude disabled persons and, thus, effectively remove them from the public domain” (p. 197).

In exposing the cultural and institutional context in which understandings of disability and disabled individuals are embedded as well as acknowledging our own anxieties in becoming disabled, Davis encourages us to recognize that people with disabilities are not “abnormal,” “deviant,” or even all that difference from able-bodied individuals. It is this realization she hopes “may help pave the way toward a more compassionate view of persons with disabilities, and of ourselves as embodied human beings” (p. 213).

Great Articles, Part 4

In no particular order, these are some of the best articles on mental illness I have read recently.

The Americanization of Mental Illness by Ethan Watters (New York Times Magazine)

Ethan Watters argues that Western thinking about mental illness has gained a foothold around the globe thanks to the aggressive promotion by both the psychiatric and pharmaceutical industries. In the process, Western diagnoses have increasingly taken the place of traditional experiences and explanations for mental illness. Quoth Ethan:

For more than a generation now, we in the West have aggressively spread our modern knowledge of mental illness around the world. We have done this in the name of science, believing that our approaches reveal the biological basis of psychic suffering and dispel prescientific myths and harmful stigma. There is now good evidence to suggest that in the process of teaching the rest of the world to think like us, we’ve been exporting our Western “symptom repertoire” as well. That is, we’ve been changing not only the treatments but also the expression of mental illness in other cultures. Indeed, a handful of mental-health disorders — depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anorexia among them — now appear to be spreading across cultures with the speed of contagious diseases. These symptom clusters are becoming the lingua franca of human suffering, replacing indigenous forms of mental illness.

Cross-cultural psychiatrists and anthropologists have argued through their research on mental illnesses that these disorders are not discrete entities like viruses that have their own natural history. Instead their research findings tell them that mental illness has never been uniformly the same across the globe, either in the form the illness takes as well as the rate at which it affects others but are “inevitably sparked and shaped by the ethos of particular times and places.”

It’s not surprising to me that many mental disorders are the result of the numerous socially accepted ways we fuck each other up.

Overall, I agree with Watters in his assessment that manifestations of mental illness are shaped by local culture and customs, that people are presenting with symptoms that suggest Western-style depression and schizophrenia in places where they have been unrecognized in the past, and the pharmaceutical industry is aggressive in promoting the diagnosis of diseases for which it sells treatments. At the same time, isn’t it the manifestations that are culturally bound, but not necessarily the disorders themselves? Depression, schizophrenia, OCD, anorexia: I still believe that these are real entities no matter which culture you observe. That’s not to say that the etiology of the disturbance does not differ by culture. I also have a hard time buying his argument the premodern societies are somehow less stressful than modern ones. Still, this is a fantastic article that was published this prior to the release of Watters’s book, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche.

The Therapist Who Saved My Life by Ella Wilson (Literary Hub)

This essay is gorgeous.

After many suicide attempts, a variety of diagnoses, and even more prescriptions, Ella Wilson was ready to give up.

I have been diagnosed with bipolar II, borderline personality disorder, anorexia, unipolar depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and treatment-resistant depression. These have been countered with Paxil, Effexor, Remeron, Klonopin, Xanax, Prozac, Zyprexa, Seroquel, Abilify, Lexapro, Celexa, Chinese herbs, electroconvulsive therapy, hypnosis, leafy greens, fish oil, vitamin B12, St. John’s wort, group therapy, light therapy, talk therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and acupuncture. But none of these things helped. There was no way they could. You cannot fix someone who does not feel connected to the idea of living with a pill, any more than you can fix a car without wheels by filling the washer reservoir with blue liquid.

Then she met a woman who would pull her back and make her feel of this world again. This woman was her therapist. A very unconventional therapist and many would say a very unprofessional therapist. But effective when nothing else was. Wilson explains:

The only way to come at a problem of this magnitude and confusion is not with sense; it is not with reason or science; it is not with pills or lists, electrodes or clever sayings. A problem of this scale and unnameability needs to be met with nonsense, with moonshine and malarkey. With magic and oracular thinking. Insanity meeting insanity.

Ella engaged in a different kind of therapy, the kind of therapy “they don’t teach at therapy school.”

This therapist was not treating me like another client. She was doing more for me than therapists did. And this did not scare her. She was wonderfully unafraid to like me, to love me, to share her story with me, to walk down the street with me, to want me alive, to care for me. And this lack of fear on her part vibrated as she held my hands and smiled into me. We can do this.

Ella describes her therapist as a connector (as opposed to a professional nodder).

She did not leave me in my pain and sadness, she brought her own out to the moorlands that howled with wind and nothingness and sat down across from me. She offered up her fears and devastations as anchors. Her scars made her a believable hero. She was just the kind of woman who might change someone’s life.

Insane. Invisible. In Danger. by Leonora LaPeter Anton, Michael Braga, and Anthony Cormier (Tampa Bay Times and Sarasota Herald-Tribune)

This investigative report on Florida’s mental health care system won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s so deserved. This is a must-read series that sheds light on the dark and grim realities inside Florida’s mental health hospitals. The accounts of deplorable conditions are harrowing. Florida ranks 49th in state mental-health agency funding per-capita. This series shows how funding and staff shortages contributed to unhealthy and dangerous conditions in the state’s mental hospitals. The reporters documented how the safety and lives of patients and staff were at great risk.

The stories (and accompanying surveillance videos) are devastating: staffers alone on the wards being brutally beaten or stabbed by patients; patients with no protection being killed—in one case stomped to death—by other patients; patients with life-threatening injuries ignored until it was too late to save them; 1,000 patients who have injured themselves or others over five years; and the relentless bureaucratic neglect amid draconian budget cuts that enabled it all. Not to mention the “wall of secrecy” protecting the hospitals and abusive workers that the two papers spent more than a year trying to penetrate.

The reporters immersed themselves in the day-to-day realities of the state’s six main mental health hospitals and discover their disturbing secrets. These reporters spent over a year investigating life in these mental hospitals including interviewing patients, their families, and examining numerous official records as well as hospital and police records. They found:

- Over the past five years, at least 15 people died after they injured themselves or were attacked by other patients. One man with a history of suicide attempts jumped off the eighth floor of a parking garage. Another was stomped to death because no one separated him from rivals even though they had beaten him up the night before.

- Staffing shortages so acute that violent patients wandered the halls unsupervised.

- Employees left alone to oversee 15 or more mentally ill men. Sometimes they carried no radio to call for help, with the nearest guard in another building or on another floor.

- Even when patients were placed under special watch, they were still able to swallow batteries and razor blades or hoard weapons to use on other patients. At a hospital in Florida City, a patient needed nothing more than a stack of paper to break out of his locked room and stab his neighbor 10 times. As the man bled on the floor, a staff member, unaware of what had happened, helped the attacker wash his bloody clothes.

- Florida has no statewide minimum staffing requirements. And there are virtually no repercussions for administrators, even when someone dies. State regulators have fined the hospitals a total of $2,500 in the past five years. One hospital paid $1,000 after a patient escaped and was run over by a truck.

- At least three people died because hospital workers took too long to call 911. Some employees said they felt pressure not to call paramedics because of the expense. Others said they were required to track down a supervisor first, leading to delays.

The series was so powerful that it prompted change from lawmakers who appropriated an extra $55 million toward fixing systemic problems in the mental health care system. This is truly important and impressive reporting that is truly a public service. Extraordinary work.

Madness and the Muse by Tom Bartlett (The Chronic of Higher Education)

“We’re captivated by the idea of the troubled genius. But is it a fiction?”

And is it tenable? Is it safe?

Tom Bartlett explores Nancy Andreasen’s evidence that mental illness corresponds with creativity. A psychiatry researcher, Andreasen presented the results of her landmark study that found that 8 out of 10 writers had experienced some form of mental illness in their lives.

For more than a decade, Andreasen interviewed and tracked 30 faculty members from the renowned writing workshop at the University of Iowa, where she is a professor of psychiatry. She also interviewed and tracked 30 control subjects of similar age and IQ who worked as administrators, lawyers, social workers, and so on. She questioned and diagnosed subjects using a methodology she devised. Instead of identifying a passel of schizophrenic novelists, Andreasen stumbled on extremely high rates of mood disorders like depression and mania among the writers. The gap between the writers and the control subjects was huge: Eighty percent of writers reported some mental illness compared with 30 percent of nonwriters.

This research paved the way for Kay Redfield Jamison, who in her book, Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, examined 47 prominent poets, playwrights, novelists, biographers, and artists and found that a significant portion of them had mood disorders.

However, not everyone agrees. Other researchers argue that the evidence is lacking and have suggested that creativity is more associated with psychological stability. One of Andreasen’s stanchest critics is Judith Schlesinger who authored The Insanity Hoax. I tend to agree that the “mad genius” stereotype is not only simplistic and underdeveloped, it is also risky. The concept of a mad genius suggests that treatment kills creativity and as a result most people who believe this will not seek psychiatric treatment because they fear losing this elemental part of their lives. Patients who resist treatment are at serious risk for death by suicide.

Those who are high-functioning and productive may find that their volatile and destructive symptoms give them a characteristic authenticity, a raw-nerve emotional oomph and they may resist treatment. It may take a rock bottom attempt at self-harm to get them to accept the severity of their illness. And it may in some cases be too late. Relinquishing the idea that romanticized capital-M Madness makes one more productive and authentic instead of identifying as someone who has an illness can be difficult and unsexy, but it may be the key to saving their life.